Estrela's African Land Adventure Journal

Day 91. August 30, 2008. Gochas, Namibia to Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa. Camping at Mata Mata Rest Camp. (25º45.970’S 022º00.035’E).

Elevation: [unrecorded].

We woke before sunrise, took down the tent, and ate breakfast on the steps outside the bathrooms (Pic 1).

When we were checking out, I asked Mom to take a picture of the zebra hide sprawled on the floor of Auob’s main lodge building (Pic 2).

I thought it was quite disrespectful to the zebra to have its skin, including the head, lying on the ground where people walk.

We left Auob Lodge and drove into town to buy our next week’s supplies at the OK Grocer grocery store (Pic 3).

Mom and Dad piled groceries on top of Eliza and me until we could hardly move. This is what happens whenever we do a big shop.

We passed two trees each loaded down by huge sociable weaver nests. A little while later, we were just about to pass a dead animal on the road when I asked Dad to stop so that I could identify it. I got out of the car and walked over to it, quickly realizing it was a bat-eared fox (Pic 4).

These dog-like animals eat Termites, other insects, scorpions, sunspiders, small rodents, reptiles, small birds, and fruit. They do not kill livestock, as farmers wrongly believe. Bat-eared foxes are very playful. Even the adults like to play. They play with sticks, feathers, and each other. A bat-eared fox has even been seen playing with a bontebok (a type of antelope). So it was very sad to see a bat-eared fox dead on the road, covered in flies.

At the border we left Namibia and entered South Africa and the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (Pic 5).

[editor’s note: “Kgalagadi” is pronounced basically the same as “Kalahari.” The “g” is a soft sound as in “gemsbok,” which is pronounced almost, “hemsbok,” except that the “h” sound feels like a throaty cat’s hiss.] We set up camp right next to the animal fence. Then we went out for a drive inside the park before dinner, but because the roads were terrible we had to drive slowly and couldn’t get very far. We saw many springbok and blue wildebeest, two ostriches, six giraffes, one gemsbok, and many birds. On the way back we listened to “Dune.” I couldn’t wait to go game-viewing in the morning.

-- Abigail C.

Day 92. August 31, 2008. Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa.

Camping at Mata Mata Rest Camp. (25º45.970’S 022º00.035’E). Elevation:

[unrecorded].

We left the camp early and drove down the terribly corrugated, sandy road, looking for animals, and wondering when the road had last been graded. The Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park is known for its network of 4×4 trails through the bush, which supposedly give a “true Kalahari experience.” For us 2×4ers, there were only four roads we could use in the entire park, all of exceptionally poor quality. Unlike in Kruger or Etosha, we couldn’t explore much of the terrain.

As we drove along the one road leading from Mata Mata, we wondered why we weren’t seeing many mammals. Abby and I began singing, “Where Have All the Springbok Gone.” When we stopped for lunch at a picnic site and asked the other visitors what they thought about the lack of animals, they said they felt exactly the same as we did – surprised and curious – because usually there is more wildlife around. They were South Africans, too, not foreign tourists, meaning they knew their game parks.

But this is not a zoo, we agreed; that’s the reality and a big part of the attraction of these enormous southern African national parks. We were just lucky we weren’t typical tourists on a week-long holiday from Europe; we’d already had almost twenty days of animal-jammed game-viewing in Etosha and Kruger alone. So it was easy to shift our focus to birds.

Birds are fantastic. There are so many different species that you could spend your entire life bird-watching and not see all of them. But with mammals and other large animals, there are relatively few species, and most are usually easy to spot because they’re larger and rarely airborne. One of the best parts about birding is that you really have to keep a sharp lookout for slight movements, which means you’re more observant and will most likely see larger animals you might otherwise have missed.

Every time I look up a bird in our main bird field guide, “Newman’s Birds of Southern Africa,” I am amazed by how many similar species and sub-species and sub- sub-species there are. It’s mind-boggling that anyone can distinguish all of them. For example, the members of the cisticola family, small, brown, grass warblers, are so similar that on one page, the note at the top warns readers that “accurate field identification based on plumage alone is almost impossible.”

Here are some birds we saw today: two swallow-tailed bee-eaters perched near a Namaqua dove (Pic 1),

a marico flycatcher (Pic 2),

and an ostrich (Pic 3).

The last picture is of ostrich spoor showing the strange structure of its asymmetrical two-toed foot (Pic 4).

-- Eliza

PS – We finished listening to Dune this evening on the way back to camp.

I’m sad that it’s over, but at least now we can concentrate on animal-watching without being distracted by the book.

Day 93. September 1, 2008. Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa.

Camping at Twee Rivieren Rest Camp. (26º28.459’S 020º36.769’E). Elevation:

[unrecorded].

Today we moved camp from Mata Mata to Twee Rivieren, 120 kilometers south on the main road which meandered down the middle of the Auob River’s perennially dry riverbed. The Auob last flowed in 2000, and before that, in 1974.

We drove slowly, looking for birds, small mammals we hadn’t seen before, and even an historic site marked on the guide map. After two days in this park we figured we’d seen all the species of large mammals we were going to see.

Big cats, in particular were off the agenda, we realized. Sure, we’d heard that a few other park visitors had caught glimpses of cheetahs and a leopard this week, but the general buzz was that animal viewing, inexplicably, was in a funk. Something had changed. The large herds, which others had encountered in previous visits, were nowhere to be seen. Maybe that was why large carnivores seemed scarce.

Strangely, however, we felt relieved. The pressure was off. Yes, we would love to see cheetahs, a leopard or lions again. This park would most likely be our last opportunity to observe these iconic African creatures in the wild. But we had seen them all at least once in another park and, anyway, we didn’t want to be greedy. We’d seen others get caught up in big cat viewing acquisitiveness. We’d felt ourselves start to go down that path.

Always wanting to see more cats, closer cats, cats stalking or eating prey, or the ultimate, cats killing, you’re never satisfied. This hunger for more has been an exciting aspect of game viewing for us. But individually, each of us had come to realize on our own that it didn’t feel right to focus primarily on acquiring more, new, or better sightings. It wasn’t healthy. And we’d be missing out on the richer educational and spiritual fruits of visiting these magnificent African parks.

We had begun to enjoy our sense of release, no longer burdened by the feeling that if we just tried a little harder, looked more observantly, woke up earlier, or stayed out longer, we’d see more of the coveted big cats.

The big cats must have gone away. That was okay. Some of our tension had dissipated. So perhaps it was this new game-park-zen that led us to stop and watch a meerkat community for 20 minutes this morning, exhibiting all the behavior described in our guidebook. We were charmed. We couldn’t get enough. Here is a photo of two sentinel meerkats, keeping sharp watch for predators while their clanmates emerge from the warren, stretch and yawn, and set off to forage (Pic 1).

We learned that some meerkats volunteer to remain behind as babysitters, thereby gaining social status by sacrificing their personal opportunity to eat. Others take on a mentor role, accompanying apprentices learning to forage, again, giving up some of their own feeding time for the greater clan good, strengthening clan bonds. Abigail, an avid reader of the “Warriors” series, which tells exciting tales of wild kittycat clans, noted many parallels with the meerkat world. She was on fire.

We crawled to Twee Rivieren. Often, as soon as the car went faster than about 20 kph it began a rhythmic bouncing, triggered by the badly corrugated road surface. Even for a low-slung 2WD sedan, though, this seemed extreme behavior. [editor’s note: Weeks later we’d learn that the front shocks had failed completely, probably around this time. We were driving on the front springs alone.] But it gave us plenty of time to observe our surroundings carefully. Memorable sightings were a secretary bird, well over a meter tall, strutting regally across the road (Pic 2),

an African hoopoe (Pic 3),

a red hartebeest (Pic 4),

a reconstructed spartan homestead of early European settlers (Pic 5),

and a northern black korhaan (Pic 6).

Late in the day, just before Twee Rivieren, we turned north on the park’s other main road, which runs up the even drier Nossob River’s riverbed. We wanted to scout the road’s condition, having heard the rumor a grading crew was working on it. We drove a few kilometers and found happily that it was in much better shape than the Mata Mata road. Turning for camp, we stopped to watch a peculiar sight, mating ostriches. Oblivious to our presence and close to the road, the ostriches gave us a startlingly intimate performance.

Video camera rolling and still camera snapping, we let fascination trump embarrassment. These pictures caught moments 12 seconds apart (Pics 7 and 8).

As we drove slowly into the campground area of the Twee Rivieren Rest Camp, looking around to choose an open campsite, we saw a couple sitting beside their kombi and holding what looked curiously like one of our hubcaps. Hmmm . . . Well it was, it turned out. What a great icebreaker . . . Francois and Marica Du Toit, a South African couple from near Cape Town, had found it on the side of the Mata Mata road. We didn’t even know we’d lost it. Our heroes!

-- Doug

Day 94. September 2, 2008. Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa.

Camping at Twee Rivieren Rest Camp. (26º28.459’S 020º36.769’E). Elevation:

[unrecorded].

We decided today would be a rest day, so we had a leisurely breakfast of eggs and bacon. Dad made the eggs (Pic 1),

and I made the bacon! It was SO GOOD!!! A yellow mongoose seemed interested in our breakfast too (Pic 2).

These sleek-looking carnivores have very complicated social structures. We pulled out our wildlife behavior book and read aloud pages and pages about them (Pic 3).

Yellow mongooses are now Dad’s second favorite small carnivorous mammal, right after meerkats. We spent the rest of the day washing clothes and doing dishes.

In the afternoon we went swimming in the Twee Rivieren Rest Camp’s crescent-shaped pool. Mom, Dad, and I swam, but Eliza just read her book. It was so cold that we got out immediately after jumping in. We dried off and warmed up in the sun, reading our books and eating lunch. We met some people at the pool and talked with them about Namaqualand. They said the wildflowers there were beautiful. We came back from the pool, started the fire, and cooked dinner.

-- Abigail C.

Day 95. September 3, 2008. Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa.

Camping at Twee Rivieren Rest Camp. (26º28.459’S 020º36.769’E). Elevation:

[unrecorded].

We got up early and left at 7:00. I was secretly hoping to see a lion on our last day in the park.

The first exciting thing we ran into were the spoor (paw prints) of at least three lions (Pic 1).

We followed them until we came upon a pair of sleeping Verreaux’s (or giant) eagle owls (Pic 2).

These grey giants grow to be 60-65 cm tall. They have pink eyelids and dark brown eyes. These big guys may sound cute, but they are probably some of the fiercest airborne hunters of the night. We left them and resumed tracking the lions.

A few minutes later, two people in a car drove up and said that a pride of lions with cubs was a couple of kilometers ahead lying on top of a red sand dune. We stopped when we came to a group of cars. When we looked up at the dune on our left . . . there they were! Three lionesses, three cubs, and one HUGE male lion!

The male was lying on his side with his gigantic head facing towards us. His gigantic gold-and-black mane was thick around his head and shoulders. A little cub was poking its head out of the grass next to the big guy. As we watched them, we were astonished that they took no notice of us even though you could tell they knew we were there. The massive lion stood and looked down at the cub, which looked right back at him with wondering eyes (Pic 3).

The big one turned and lay down. The little one watched his every move.

The next thing we knew, one of the lionesses was rolling onto her back, like a house cat. She stayed like that for a while with one leg in the air (Pic 4).

All of a sudden, the lion’s mane rose into the air (Pic 5).

He swiveled his noble head around, inspecting his territory. His dark brown gaze was full of wisdom; he knew the ways of the old giraffe bull, and of the springbok in their large numbers. If lions could speak, they would pour out information too vast for our minds to grasp. But he knew it all and he could still learn more. Seeming satisfied, he re-adjusted himself and lay down, vanishing behind the crest of the dune.

The lioness lowered her leg, rolled over on to her side, and raised her head. A cub walked up to her, put one paw on her shoulder, and started washing its other paw. I don’t know if the lioness was the cub’s mother, because lionesses in the same pride share the responsibility for raising and nursing the cubs. My favorite moment was when the cub flicked its pink tongue out. Mom even got a photo of it (Pic 6).

We drove on because another car told us that there were more lions off on a side road 3 kms up ahead. While we drove we saw rectangular cement posts with RSA (Republic of South Africa) on one side and RB (Republic of Botswana) on the other (Pic 7).

This was because the road was in the dried-up Nossob River bed, the border between South Africa and Botswana. It flows approximately twice every 100 years. I thought it was really neat that there was no fence between the two countries and that we were crossing

the border back and forth.

As we turned onto the side road at the Kij Kij waterhole, we saw many bones such as a hoof of some sort of antelope and the skull of a gemsbok (Pic 8).

When we got to a place where a few cars had gathered, we looked up on a small dune and there were the lions! It was a group of young males with scraggly manes (Pic 9).

We assumed they were a bachelor group. So it was surprising when we saw a lioness among them (Pic 10).

Lionesses stay in their natal prides while males, at two to three years, are expelled. They usually form small bachelor groups with young males displaced from other prides. When a male lion comes of age he leaves the bachelor group and seeks to drive out or kill the resident male of a territory and then take over the pride. But I was amazed to learn that sometimes more than one male rules a pride at the same time. Coalitions of four to six males have been observed to rule a pride for four to eight years. The coalition males are often closely related to each other, but not to the females who form the core of the pride.

After watching these lions for a while we drove to a picnic spot and had breakfast. Then we continued on to see more game. When we reached the Kransbrak waterhole we turned around and drove back to the second group of lions, passing a tawny eagle and a sociable weaver nest on the way. The bachelor group was lying all together, and only one, who had his head up, looked at us. After a couple minutes we turned around because we wanted to see the other pride again before it was too late. When we got there one of the lions was sitting in the gap between two bushes. We didn’t take any pictures because the lighting was terrible, so we drove back to camp. On the way we saw some ground squirrels, two more tawny eagles, two kori bustards, and a herd of springbok. And then we were back at our camp at Twee Rivieren. Today was a great way to end our time at the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park.

-- Abigail C.

Day 96. September 4, 2008. Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park to Augrabies Falls National Park, South Africa. Camping at Augrabies Falls National Park Rest Camp. (28º35.581’S 020º20.252’E). Elevation: 621 meters (2037 feet).

Just when we thought we couldn’t take one more minute of gravel road and blinding dust (Pic 1),

the only road out of the Kgalgadi Transfrontier Park’s southern gate turned paved. Phew. We were now officially in the Northern Cape, one of the largest and least populated provinces in South Africa and where the mighty Orange River cuts through the semi-desert terrain of the Kalahari and the Karoo. Our road map indicated ‘permanent dunes’ up ahead. I had never heard of permanent dunes, but soon it became obvious as the black ribbon of Route 360 rose and fell like a stretched-out rollercoaster over the sea of sand dunes now anchored in place by hardy vegetation (Pic 2).

There were no towns or villages, just scattered cattle ranches. We knew that we were nearing the Orange River by the sudden appearance of verdant fields. Irrigation had transformed this desolate land. We camped at the Augrabies Falls National Park (Pic 3).

We were too late to see the falls this evening. Its sound thrummed all night long.

-- Kyle

Day 97. September 5, 2008. Augrabies Falls National Park, South Africa to Kamieskroon, Namaqualand, South Africa. Camping at Cosy Mountain B&B campsite (30º11.058’S 017º56.239’E). Elevation: 816 meters (2677 feet).

We woke up early and took down the tent. Then we drove to the reception, where there was a display on the Augrabies Falls. Aukoerbis, a Khoi word, changed into Augrabies by the Europeans, means “Place of Great Noise.” Augrabies Waterfall, fed by the Orange River (the water is more murky brown than orange), is 56 meters high.

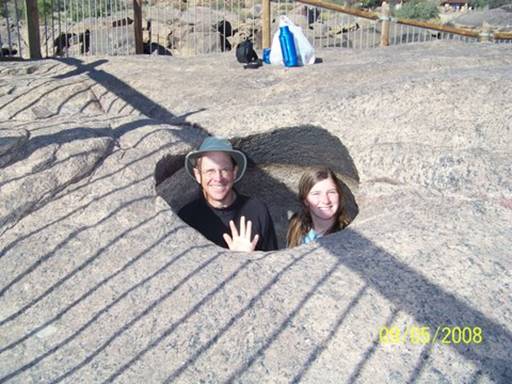

We walked down a boardwalk to one of the many platforms, where we saw the magnificent falls. On another platform Mom made us coffee and Milo from our hot water thermos that she was carrying. The path then led to an open, smooth rock area that had a few potholes scattered around. One pothole was so big that Dad, Eliza, and I got in (Pic 1 – that’s my hand).

I convinced Mom and Dad to go to another platform whose views turned out to be the nicest of them all. You had a view of the gorge as well as the waterfall (Pic 2).

On the way back we passed a patch of reeds where a male southern masked weaver was weaving his nest (Pic 3).

Then we went back to the car and left. On the side of the road was a group of quiver trees (Pic 4).

This succulent tree is a type of aloe.

The rugged scenery on the way to the town of Springbok was beautiful. The wildflowers were out (Pic 5)!

At a picnic place underneath a huge sociable weavers’ nest we stopped and ate breakfast. We drove through Springbok and then went south. Finally we got to Kamieskroon and we drove to a caravan park, but it looked like a horrible place to stay so we drove on to another place called Cozy Mountain B&B, which also had two campsites, which were far away from the house. The people were really nice and they had three dogs named Riley (a German shepherd-Rhodesian ridgeback mix) and two Jack Russells. Riley followed us to our campsite 2 kms away. I raced him (Pic 6).

Mom and Dad put up the tent while Eliza and I explored, climbed rocks, and watched rock dassie babies dart in and out of their caves. When the sun set it became very cold. Then the wind started to blow. We had to build a wall of stones around the fire so that it wouldn’t go out. Mom made potjie muffins for next morning. It was so windy that soon after we went to bed the tent was almost flattened.

-- Abigail C.

Day 98. September 6, 2008. Kamieskroon, Namaqualand, South Africa.

Camping at Cosy Mountain B&B campsite (30º11.058’S 017º56.239’E).

Elevation: 816 meters (2677 feet).

After a frightening night of thinking our battered tent was going to snap under the howling wind, we awoke to a beautiful sunrise, which painted the bushes on Cozy Mountain a vibrant green. It seemed that we had been in dry grasslands for so long we had forgotten how green a plant could be. I think we might have packed up and left, if purely for the tent’s sake and the well-being of our nerves, but the aliveness of the sunrise convinced us to stay another night.

We passed the day resting, Abby creating a sand-world by the tent, Dad and Mom planning the next leg of our trip, and me reading in the shade. At 2:30, about the latest we could consider setting off, we grabbed the flower ID book and headed for the Namaqua National Park.

This national park is in Namaqualand, the region in western South Africa world-renowned for its brilliant displays of wildflowers each spring from mid-August to mid-September. We had seen a few clumps of flowers beside the highway near Springbok, where Namaqualand begins, but according to some South Africans we’d met in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, they were nothing compared to the carpets of flowers we would see in Namaqua National Park, if our timing was good. I didn’t really believe them.

As we rounded a bend in the tortuous mountain road, the scenery ahead of us burst into color (Pic 1).

It was as though molten sunlight had been poured over the grass (Pic 2).

Thousands of orange Namaqualand daisies winked and rippled in the breeze (Pic 3).

I had never seen so many wildflowers in one place, ever. The dirt road meandered through fields of them, and I wanted to leap out of the car and roll through the blossoms, which, unfortunately, was not allowed.

Listening to this evening’s much gentler breeze as I fell asleep, I thought how lucky we were to have seen these wildflowers. If today had been rainy, as it had been for most of last week, we would not have seen anything, because the flowers only open when the sun shines.

-- Eliza

Day 99. September 7, 2008. Kamieskroon, Northern Cape Province, to Ceres, Western Cape Porvince, South Africa. Overnight at the home of friends, Francois and Marica Du Toit, Ceres, Western Cape, South Africa (33º22.154’S 019º18.497’E). Elevation: [unrecorded].

This was a day when I was glad to have lithium camera batteries and a clean windshield. It was the kind of day where the scenery was stunning and the lighting almost perfect -- a living IMAX movie, lacking only the stirring soundtrack. It was an Ode to South Africa, a land flowing with milk and honey.

We traveled south out of the Karoo on the N7, the main north-south highway between Cape Town, South Africa and Windhoek, Namibia. First traversing a stark scrubveld region dotted with majestic granite massifs (Pic 1),

we entered the Western Cape Province and dropped steeply down from a high plateau into the Olifants River Valley. Here we found one of South Africa’s most spectacular fruit regions, with town names like Citrusdal and Oranjeville. This fertile valley is flanked by north-south running mountain ranges (Pic 2).

The further south we drove, the taller and more rugged the mountains became. The highway left the Olifants valley, cut west and south again through a mountain pass and descended into the vast Berg River valley, known as the Swartland, which stretched to the horizon with lush, green wheat fields (Pic 3).

We turned east off the highway and headed towards the Skurweberge and Witsenberge mountains, snow still clinging to the highest peaks from a recent winter storm. The 2078 m (6,817 ft) Groot-Winterhoekpiek (Big-Winterhookpeak in English) and its adjacent high range dominated the landscape. Here we encountered our first vineyards. We were driving straight into the country’s world-renowned wine-producing region. The mountains felt like sentinels, guarding the precious vineyards at their feet (Pic 4).

In 1652 Commander Jan van Riebeek had led an expedition for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to establish a Cape station, a provisioning base for their ships that sailed between Holland and the East Indies, today Indonesia, by way of the Cape of Good Hope. He and his men, with East Asian slaves and reluctant labor from indigenous khoikhoi people, built a fort for the VOC and planted gardens and vines to produce food and wine for the passing VOC ships. With the arrival of the first small group of French Huguenots in 1688, serious wine-making began.

We took a quick detour to the picturesque village of Tulbagh, famous not only for its excellent wine and port, but also for its well-preserved, 18th and 19th century Cape Dutch architecture. Tulbagh has 32 historic registered homesteads on one street! It is the most complete example of a Cape Dutch village in South Africa (Pics 5&6).

We continued toward our destination, the home of our Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park “hubcap” friends, Francois and Marica Du Toit (pronounced Du Toyt). A wall of thick clouds, moist marine air pushed north by an arriving cold front, enveloped the mountains and darkened the sky as we approached Mitchell’s pass into Ceres (Pic 7).

The Ceres Valley, a veritable Shangri-la of fruit farming, is reachable only through one of three mountain passes. We arrived just as the rain started to fall.

-- Kyle

Copyright © 2003-2009 Doug and Kyle Hopkins. All rights reserved.